Conflicts¶

Eventually, a situation will arise where the logical outcome is less obvious, either because it is unwelcome (e.g. the character gets hurt) or uncertain (e.g. can the characters sneak past the guard?). This is a conflict, and it needs to be resolved.

Frame the Scene¶

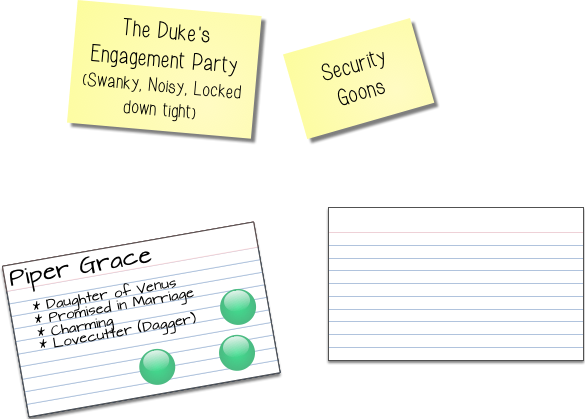

At the outset of the conflict, the GM has the option to add some aspects to the scene, by writing the aspects down on cards and putting them in the middle of the table.

Each card represents a distinct thing, like a character or a piece of scenery, and, as such, cards may have multiple aspects on them. Adding an aspect to the scene means either adding a new card or writing down an aspect on an existing card. Removing an aspect from the scene means crossing it out (and removing the card entirely, if appropriate).

It can be easiest to start with a single blank card and add two or three “environmental” aspects to it to start. You could add a card for each one if you like, but however you approach it, the way you describe a scene usually suggests the framing aspects. Dark and Warehouse suggests a very different scene than High Society Party and Swanky Penthouse.

Adding Aspects¶

The GM has a lot of leeway in adding aspects to a scene, but there are rules the GM must follow: If the aspect is detrimental to the characters (e.g. an environmental danger, an aspect on an enemy, or on a character), then the GM must pay one fate point for each detrimental aspect. However, the first aspect on a scene is free. If the aspect is beneficial to the characters (e.g. an ally or obvious advantage), the GM may take one fate point for each beneficial aspect. If the aspect is neither clearly beneficial nor detrimental (e.g. descriptors on the scene, like Thick Forest or Crowded Market) then the GM may place those for free. As a general rule of thumb, the number of cards laid down is usually a signifier of how significant the scene is. If a scene has more than 4 cards in play, it’s probably a pretty big deal.

Characters and The Scene¶

If a character is in the scene, then all the character’s aspects are considered in the scene as well, meaning they can be invoked by anyone involved in the scene. If new aspects get put on the character (for good or ill), then the aspects should be written on the character’s status card, not on the character sheet itself.

Sample Scene¶

The GM paid 2 fate points to frame this scene. The Swanky and Noisy aspects on the party are fairly neutral. If the character Piper Grace were on the invite list, Locked Down Tight would probably be neutral too, but, since she’s not, that is definitely a detrimental aspect, so the GM paid a fate point for it. The GM paid an additional fate point to add the Security Goons. Describe Action and Determine Difficulty Once the scene is framed, one of the players will describe the action their character takes.

The GM will then determine the difficulty of that action, based on the aspects in play. The difficulty starts at 0, and each aspect that clearly makes the task more difficult increases the difficulty by +2. As the GM describes the situation, she should include those difficulties as she frames the scene.

Example: In this case, Piper Grace is trying to bluff her way into the party. Locked Down Tight and Security Goons “both seem applicable, so the GM declares the difficulty is +4. Choose an Aspect The player is about to roll dice, so they start by invoking an aspect. This can be any aspect on the table that they think would help them. If there is a beneficial aspect, then invoking it grants a +2 to the character’s roll.

This first invocation costs no fate points. Each subsequent invocation costs 1 fate point.

Example: To bluff her way in, Piper’s Charming aspect seems obviously applicable, so she invokes that for free. That means she will roll at a +2, but the difficulty is 4, which is still difficult. As a Daughter of Venus, she can be very distracting, so as long as she’s willing to be a little flirty she could spend a fate point for another +2 to her roll. However, she wants to see how the scene goes before she spends anything more.

Rolling the Dice¶

Fate dice have six sides. Two of them are marked with a +, two with a -, and two are blank. When you roll the the dice, you add them up, with the +’s equalling +1, and the -’s equalling –1. So, for example: + + - = +1. Add the dice to the bonus from all invoked aspects and compare it to the difficulty. If the total equals or exceed the difficulty, then it is a success. If not, then it is a failure. But it’s not over yet! Dice Example

Making Adjustments¶

After the dice have rolled, both the player and the GM have the option of altering the situation. The player may spend another fate point and describe how an aspect on the table or the character card helps him out. The GM may reveal new aspects, adding them to the scene, or declare borderline aspects to be problems. In either case, this increases the difficulty, but requires that she spend a fate point (giving it to the affected player).

Only after this back and forth concludes is the roll resolved as a success or a failure. Invoking detrimental and beneficial aspects can feel a bit mechanical at first, but with practice it should adopt the cadence of a conversation.

Example: Piper’s player describes her approaching the guard at the door and chattering on about people in the party and how foolish she feels for having stepped out without her invitation, and can’t the guard be nice about it? The GM calls for the roll and Piper rolls + - + 0,(+1) with her invoked Charming aspect adding +2, bringing her total to +3, still one short of the target. The GM describes that she seems to be somewhere with the door guard (she had rolled well enough that she’d have gotten past if it was just one obstacle) but he abruptly draws himself upright and looks stern as one of the security officers come by. Piper’s player now has the choice of spending a fate point using another aspect (perhaps Daughter of Venus, to flirt the guard back to a relaxed state) to succeed, or seeing what the GM does with a failure.

Summary of a Conflict¶

Player describes action GM describes difficulty and assigns a value, 2 points per opposing aspect Player invokes an aspect for free (if possible) and rolls with a +2 for the invocation. Optionally: Player elaborates on the description of their action and paysspends fate points to the bowl to invoke additional aspects, adding +2 to their result for each invocation. Optionally: The GM elaborates on the scene, introducing new aspects or declaring previously benign aspect to be problems, increasing difficulty by 2. Each such introduction or declaration requires the GM give the opposing player one fate point. If the player matches or exceeds the difficulty, they succeed. If not, they fail.

Success¶

If the player succeeds, they may do one of the following:

- Add an aspect to the scene

- Remove an aspect from the scene. If that’s the only aspect on a card, go ahead and remove the card.

- Resolve the scene

Resolving the scene ends it with a particular outcome, but requires the agreement of everyone at the table. When the player resolves the scene, he describes the outcome, though the GM may ask him to restate things if he deviates too far from play.

Failure¶

If the player fails, then the GM may do one of the following:

- Add an aspect to the scene

- Remove an aspect from the scene

- Resolve the scene

- Offer a bargain

The first three options are identical to the player’s options. Offering a bargain is a special way to resolve the scene - the GM may offer the players an outcome they like (such as a resolution on their terms) but with a price. The price is either explicit (“You can make it in time, but you’ll have to leave your gear behind”) or implicit (in which case the GM gets to take a fate point from the bowl).

Continuing Play¶

If the scene is not resolved, then it has been changed in some way (for good or ill), and the players may return to describing actions and determining difficulty. If the scene is resolved, then it’s time for clean up.

Clean Up¶

The GM gathers up all aspects on the scene except those on the character’s status cards. Anything ephemeral should be discarded, but aspects which might be relevant if the situation comes up again should be set aside and saved. If they come up again (such as a fight in the same location, or an encounter with the same supporting character) then the GM adds them to that scene. Players also remove any aspects on their status card which would go away with the scene change (erase or cross them out), but others may linger until the situation explicitly changes them (such as medical care to remove a wound).

The Next Scene¶

Once the scene is resolved, the GM goes back to describing the situation, with players describing their actions and the GM describing reactions. Eventually there will be another conflict, and the process repeats.

Speeding Up Simple Conflicts¶

Sometimes the resolution will be a simple answer to a question. If the uncertainty was whether or not the character could do a thing, then the roll resolves it, simple as that. Setup and cleanup are skipped, and the GM simply derives difficulty from the scene as presented, and the only possible outcome of the roll is resolution or Offering a bargain. If anyone wants to spend points to change the situation, that may be cause to do a full scene.